Fixing drawings onto glass has been a long and challenging journey. I had been working with the Rio Grande as an artistic medium since 2017. The idea to incorporate light into the images through translucent substrates first came to me in 2020. My initial attempts involved drawing directly onto transparencies with gum arabic and fixative to hold the charcoal in place. These were the initial drawings on transparency and glass. The drawings were extremely difficult to produce offering limited consistency.

Wanting a more reliable method, I began researching ways to chemically bond carbon powder to clear surfaces. I experimented with creating my own powder from river charcoal soot and considered printing onto transparencies using a repurposed laserjet. Eventually, I discovered the carbon print method, a nineteenth century photographic technique.

Despite extensive online research, my early attempts were largely unsuccessful. Real progress came in the summer of 2025, when I spent several days in Slovenia with photographer Borut Peterlin, learning the carbon print process firsthand. Reproducing it back home turned out to be one of the most difficult and expensive artistic projects I have ever undertaken.

I built a darkroom to prepare and expose light sensitive plates. Each attempt took several days, involving steps such as grinding charcoal, mixing chemicals, pouring glop, drying tissues, cleaning surfaces, making negatives, exposing, and transferring the image to a permanent surface. It took at least ten to fifteen pours before I achieved a successful result. The complexity of the process is hard to put into words, but anyone who has tried it will understand. There were times I considered abandoning the idea altogether, but my stubbornness and fascination with the process kept me going.

Most of my early results ended up discarded. The tissues often failed to release properly, flaked apart, or simply would not transfer. The video here shows a record of those attempts, from the earliest transparency drawings to the many failed trials of the summer. It stands as a visual memoir of both the struggle and the progress that led me forward.

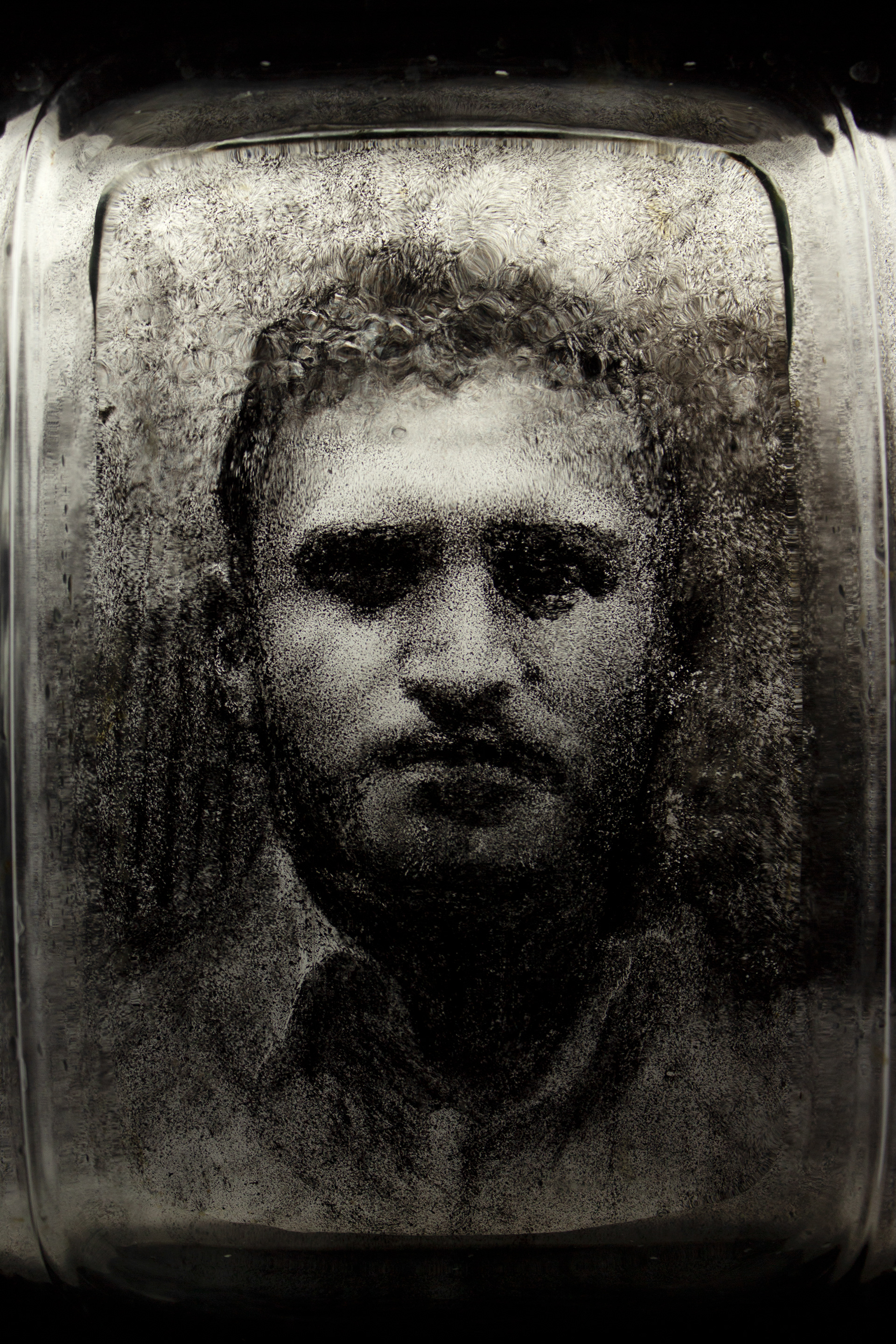

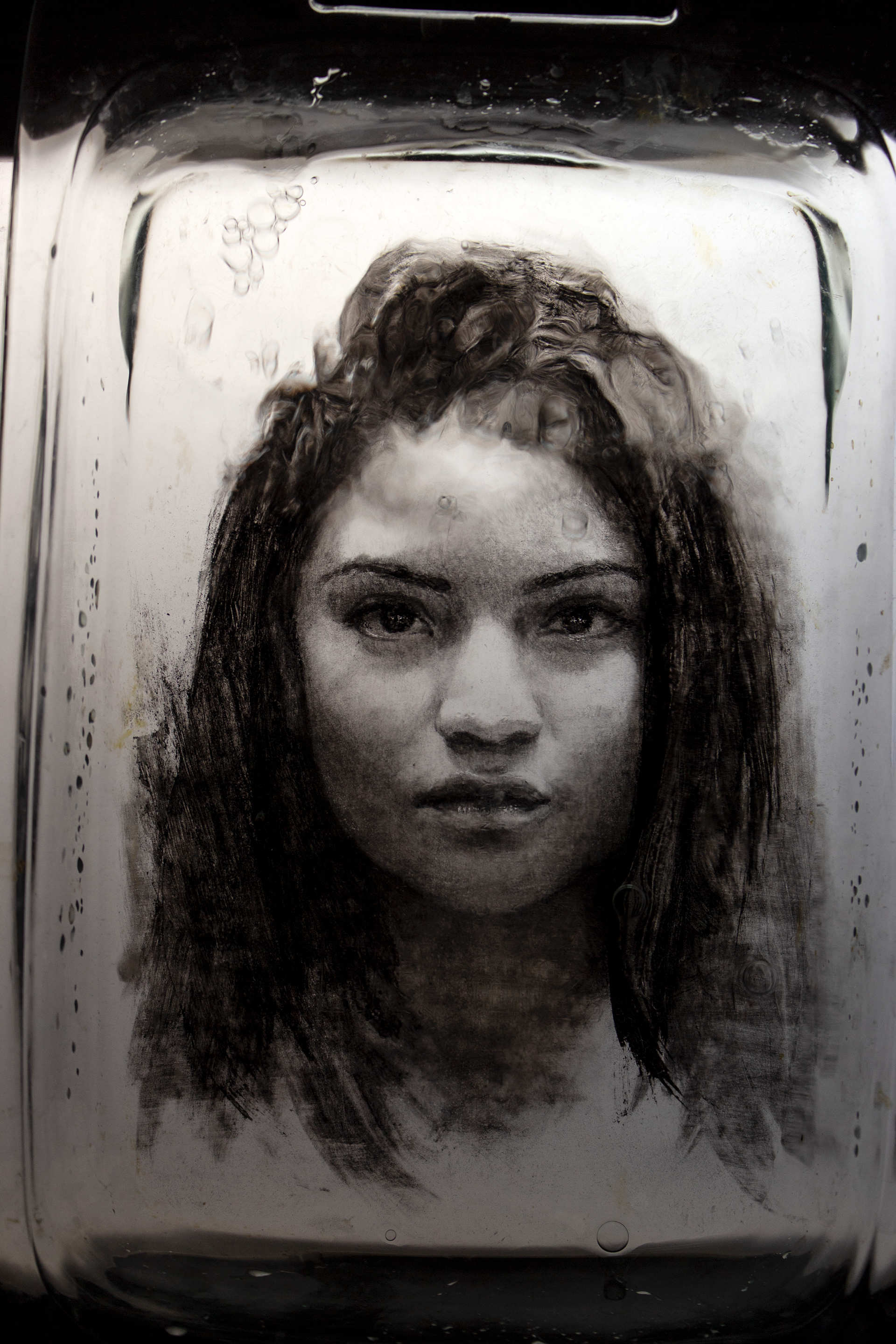

After much trial and error, I’ve become proficient enough with the process to control its variables and reach the results I want. Each work begins with a drawing that can take days or weeks, depending on its complexity. I then prepare the light-sensitive plates using a “glop” made with Rio Grande as part of the recipe. The plate is formed by exposing a negative of the drawing onto light-sensitive "tissues" and transferring it onto glass. I call them carbonic drawings, as they exist somewhere between carbon prints and drawings.

Video explaining the process

The Glop Formula

Because the dichromate is always a low number, the best thing to do is pre-mix a solution. This is also safer since dichromates are highly toxic and more dangerous in powder form.

Pre-mix a 1 liter solution with 50 grams of dichromate and 5 grams of sodium hydroxide (caustic soda). This creates a 5% solution.

The formula I have been using is a 3/3/300

Gelatin is 3% of mixture

Sugar is ½ of gelatin

Dichromate is 3% of gelatin (caustic soda is 10% of dichromate)

Ink is 300% of Gelatin

Thus:

For a 225ml batch of glop, the recipe would be:

•6.75 grams gelatin

•3.38 grams of sugar

•4.05 ml of dichromate solution (should be 3% of powder dichromate, but we are using the formula to convert dichromate powder to the 5%solution; (100xdichromate#)/5(%))

10.25 grams of ink